Technical Reporter

ixi

ixiThey look like a pair of regular glasses – but these are the specifications of the technical packaging.

Niko Eiden, CEO and co-founder of Finnish glasses company IXI, secures the frame with a lens containing LCD in the Zoom phone, meaning their vision correction characteristics can be changed at any time.

This pair can correct the field of view of people who usually use completely different glasses to see up close.

“These LCDs … we can rotate them with an electric field,” Mr Eiden explained.

“This is completely free to adjust.” The position of these crystals affects the light passing through the lens. The built-in eyeliner shooter allows the glasses to respond to any corrections required by the wearer at a given moment.

But the history of glasses full of technology is difficult – take Google’s “glass” smart glasses with bad luck.

Mr Eden acknowledged that consumer acceptability is key. Most people don’t want to look like robots: “We need to make our products actually look like existing glasses.”

ixi

ixiThe glasses technology market is likely to grow.

Presbyterians are an age-related disease, so it is difficult to focus more on what is close to you, and as the world population ages, it is expected to become more common over time. Myopia or shortsightedness is also on the rise.

Glasses have remained the same for decades. A bifocal lens (usually two areas of myopia or vision), requires the wearer to guide his vision through the relevant area based on what they want to see so that it can be clearly seen.

Varifocals works similarly, but the transition is smoother.

In contrast, an autofocus lens is expected to spontaneously adjust some or all of the lenses, and can even adapt to the wearer’s vision over time.

“The first shots we produced were horrible,” Eden admitted frankly.

He said these early prototypes were “hazy” and had significantly poorer lens quality at their edges.

But the newer version is promising in testing, Mr Eiden said. For example, participants involved in the company’s trials were asked to read something on the page and then look at the distant subjects to see if the glasses responded well to the transition.

Mr Eiden said the eye tracking device inside the glasses could not determine exactly what the wearer thinks, although certain activities (such as reading) could in principle be detected due to the nature of eye movements associated with them.

Product Director Emilia Helin said that because these glasses react so quickly to the wearer’s eye behavior, the frame is very important.

Given the exquisite electronics inside, the IXI’s frame is adjustable, but largely adjustable: “We have some flexibility, but not enough flexibility.” That’s why IXI wanted to make sure the small number of frames it designed fits in a variety of faces.

Mr Eiden said the small battery of the IXI autofocus frame endocrine should last for two days, adding that the wearer can charge overnight when he falls asleep.

But he won’t be attracted to the release date, he intends to reveal later this year. As for the cost, I asked him if he had thought of £1,000. He just said, “I’m smiling when you say it, but I won’t confirm it.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesParamdeep Bilkhu, a clinical consultant at the Optometrists College, said autofocus lenses can help people who fight Varifocals or Bifocals.

However, he added: “There is not enough evidence to show whether their performance is the same as traditional choices and whether it can be used for safety tasks such as driving.”

Chi-ho, an optometry researcher at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, has similar concerns – what if vision correction goes wrong or there is a slight delay when he performs surgery on someone?

He added: “But, in terms of general use, I think it’s a good idea to focus on what you can automatically.”

Mr Eiden pointed out that the first edition of his company’s lens will not change the entire lens area. “People can always browse dynamic areas,” he said, adding that if a completely self-adjusted shot appears, security will become a “more serious business.”

In 2013, British company Adlens released glasses, allowing wearers to manually change the lens’s optical function through the small dial on the frame. These lenses contain a liquid-filled film that changes its curvature when in response to dialing adjustments.

Adlens’ current CEO Rob Stevens said the specifications were sold in the U.S. for $1,250 (£920) and were “been praised by consumers”, but not many opticians, saying he “strangled the sale”.

Since then, technology has evolved and the concept of automatically refocusing itself without manual intervention has emerged.

Like IXI and other companies, Adlens is working on glasses that do so. However, Mr. Stevens refused to confirm the release date.

Oxford physicist Joshua Silver founded Adlens but no longer worked for the company.

He came up with the idea of a 1985 fluid-adjustable lens and developed glasses that could be adjusted to the wearer’s needs and then set up as a prescription permanently.

This lens gives approximately 100,000 people accessing vision correction technology in 20 countries. Professor Silver is currently seeking an investment called Vision that will further launch the glasses.

As for the more expensive, electronically-filled autofocus specs, he questioned whether they would have widespread appeal: “No [people] Just go read glasses, which more or less do the same for them? ”

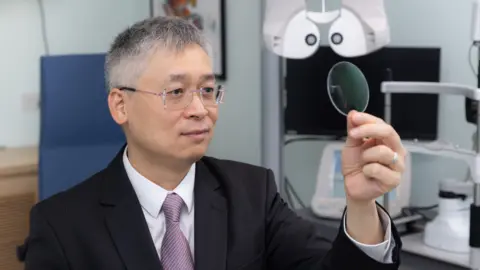

Hong Kong Polytechnic University

Hong Kong Polytechnic UniversityOther specification techniques are even slowing down the progress of eye conditions (such as myopia) rather than just correcting them.

The professor has developed glasses lenses with honeycomb rings on them. The light passing through the center of the ring is normally focused, reaching the wearer’s retina and allowing them to see clearly.

However, the light passing through the ring itself is slightly emitting, which means that the image of the peripheral retina is slightly blurred.

This seems to slow down the growth of improper eyeballs in children, the professor said, reducing the speed of short-distance progress by 60%. He added that there are now more than 30 countries using glasses with the technology.

The UK’s solid vision mirror approach is slightly different – glasses gently lower the contrast of someone’s field of view to similarly affect eye growth and myopia progression.

While autofocus glasses and other high-tech solutions may have promises, the professor’s goal is a bigger goal: not only will slow down myopia, but will actually turn its glasses a little bit—a tempting prospect that could improve the vision of potential billions of people.

“There is increasing evidence that you can do this,” the professor scoffed.